History of Drug Treatment

The face of addiction, the perception of those battling addiction, and the treatment of drug addiction have changed a lot throughout the years in the United States. The most recent national survey, which was completed in 2013, published that 24.6 million Americans (over the age of 11) were considered current illicit drug abusers and had used an illicit drug in the month before the survey, and 21.6 million people were considered to have a substance abuse or dependency issue in the previous year.[1]

Those addicted to drugs have been vilified, criminalized, or subjected to many questionable “cures” over the years, as the public and medical concept of addiction has been rather fluid. The current definition of addiction postules that it is not a failing of moral character, but rather a disease of the brain that impacts the reward system, willpower, and emotional regulation of a person. Addiction requires specialized treatment for recovery and to avoid episodes of relapse.[2]

Addiction today is thought to be the result of genetics, biology, and environmental influences. A combination of pharmacological and behavioral treatment methods may prove beneficial. Treatment can be found at one of the more than 14,500 addiction treatment programs in the United States.[3] Addiction and drug treatment in America has come a long way over the centuries and continues to evolve with the introduction of new research and scientific evidence.

Rise of Addiction in the US and the Need for Treatment

During the Civil War, opioid drugs were dispensed freely for all kinds of medical ailments. Since opioid drugs are highly addictive, this may have given rise to the spread of drug addiction in the United States following the war.[4] Before this, it is likely that people addicted to mind-altering drugs were considered a scourge to society and likely part of the undesirable “underground,” comprised of gamblers, prostitutes, and criminals. Drug addiction may have been relatively uncommon and possibly perpetuated in Chinese opium dens.[5]

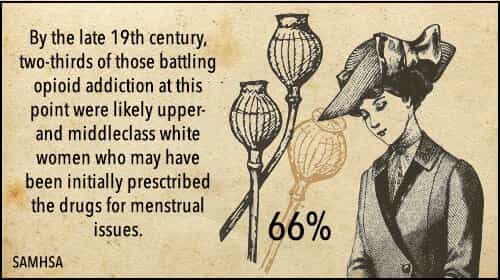

Opioid drugs were used to treat a variety of medical issues and injuries during and after the war. By the late 19th century, Civil War soldiers comprised a number of those addicted to opioids; however, large-8 medium-12 columns of those battling opioid addiction at this point were likely upper- and middleclass white women who may have been initially prescribed the drugs for menstrual issues.[6] Drug addiction was no longer confined to those considered morally dysfunctional. The estimated 300,000 people addicted to opioids in America may have been treated with sympathy and been prescribed more opiates or sent for a “cure” at a sanatorium.[7]

Individuals suffering from alcoholism or drug addiction may have been confined to an inebriate asylum for a period of time to help them “dry out,” as treatment may have focused primarily on detox, withdrawal, and physical stabilization.[8] The New York State Inebriate Asylum, built in 1858, actually may have been one of the first institutions to attempt to treat alcoholism as a disease, catering to the upper-crust society of New York in the late 19th century until such belief was shunned. The government-run treatment center was forced to close and later reopen as a psychiatric hospital for the “chronic insane” where it employed heinous treatments like prefrontal lobotomies, hydrotherapy, and electroshock therapy.[9] Inebriate asylums and sanatoriums kept patients onsite, likely even against their will, for a variety of different addiction treatment methods that in today’s times might even be viewed as barbaric.

Methods Used for Treating Drug Addiction over the Years

1800s: Addiction may have mostly been related to alcohol or opium; these substances may have been replaced with morphine, cocaine, or other supposed “medications” during addiction treatment.[10]

1800s: Addiction may have mostly been related to alcohol or opium; these substances may have been replaced with morphine, cocaine, or other supposed “medications” during addiction treatment.[10]- 1879: The Keeley Cure, or the “Gold Cure,” was introduced. This involved injecting solutions containing gold, strychnine, and alcohol into those battling alcohol, narcotic, or nicotine addictions. By the end of the 19th century, there were over 200 Keeley Institutes administering this cure. Although the injections may have been useless, these institutes may have built the foundation for group therapy and community support organizations.[11]

- 1800-1900s: The use of warm or cold water to “shock” the system with hydrotherapy may have been used to treat addiction to alcohol; it was commonly used to treat mental illness.[12]

- 1900s: Addiction may have been tied to seasonal affective disorder, or winter depression, wherein individuals may have been depressed by the cold, dark weather of winter that was thought to possibly cause addiction and may have been treated with heat lamps or light boxes.

- 1900s: Bromide-sleep therapy was introduced to treat addiction wherein individuals were put into a bromide-induced coma to wake up “cured” from addiction.[13] This method likely had a high death rate.

- 1909: Attempts to “cure” drug addiction and alcoholism were made with the deadly nightshade plant belladonna that may have induced hallucinations.[14]

- 1899-1903: Antibodies to alcohol, derived from horse’s blood, were introduced via cuts in the skin to those addicted to alcohol. Equisine was introduced, and soon discarded, as a potential vaccine for alcoholism.[15]

- 1907: Several states forbid marriage for individuals battling addiction. Sterilization may have even been performed to keep those addicted to substances from procreating and perpetuating addiction into the next generation.[16]

- 1927: Individuals addicted to drugs may have been intentionally given a large dose of insulin that would put them into a coma by raising their blood sugar to dangerously high levels with the hopes that they would wake up “cured” of addiction.[17]

- 1930s- 1950s: Criminal offenders who suffered from addiction and were housed in the Colorado State Penitentiary were infected with blisters on their abdomens that were then drained. The resulting fluids were re-injected into their arms as a “cure” for addiction.[18]

- 1935: Medical withdrawal may have been managed with codeine or subcutaneous morphine injections.[19]

- 1935: Aversion therapy for alcoholism was introduced at the Shadel Sanitorium in an attempt to condition individuals to dislike anything to do with alcohol. This therapy involved introducing unpleasant stimuli every time alcohol was presented, possibly by inducing nausea and relating it to alcohol intoxication.[20]

- 1940-1950: Addiction was considered to be caused by a dysfunction in the endocrine system, and individuals suffering from addiction were injected with adrenocorticotropic extracts from the adrenal gland.[21]

- 1948-1952: Addiction and addictive behaviors were tied to the prefrontal cortex. Frontal lobotomies, or the surgical removal of the frontal lobe of the brain, were performed on individuals addicted to drugs or alcohol.[22]

- Mid-1950s: Electroshock therapy (ECT), where individuals were repetitively shocked with wires attached to their heads and bodies, was performed on individuals battling addiction.[23]

- 1950-1960: LSD, the hallucinogenic drug, was used to treat individuals suffering from alcoholism.[24]

- Present day: Even today, the Internet gives rise to a plethora of strange and aversive techniques and “cures” for addiction that can not only make people sick, but are also largely ineffective.

Early Criminalization of Addiction and Negative Effects on Treatment

During the mid to late 1800s, cocaine, chloral hydrate, chloroform, and cannabis became widely prescribed and used, and addictions to these drugs, as well as to opioids, grew.[25] Society as a whole may have looked the other way and felt that since a large majority of those addicted to these narcotic drugs were upper-class white women, and therefore were not a threat to society, their drug addiction may have been largely tolerated.[26] Things began to change, however, as the United States became more of an international power, and drug abuse internally became less acceptable to the outside world. Physicians were also beginning to understand the potential dangers of drug abuse and addiction, and change in the population of individuals addicted to drugs may have forced the hand of the government to enact legislation controlling the prescription, sale, and abuse of narcotics.[27]

Public perception began to change as drugs increasingly found their way into urban, poor, and minority populations. Society perpetuated the idea that drugs were the cause of many criminal acts, including rape, committed by this demographic and cited drug abuse as one of the main reasons. In concern for the safety of women and children, and the growing domestic drug and narcotic drug problem, politicians may have taken notice.

In 1914, the Harrison Act was passed, which regulated the importation, sale, and even prescription of narcotics.[28] Physicians were no longer allowed to prescribe opiates for maintenance purposes, and individuals addicted to these drugs may have been left to withdraw painfully on their own or commit criminal acts to try and obtain these drugs illegally. Doctors were also arrested for prescribing opioids if they were not deemed medically necessary, and physicians were no longer able to treat those addicted to opioids with maintenance doses out of their offices directly.[29]

Prohibition in the 1920s sought to remove alcohol and mind-altering substances from society overall, although this was found to be ineffective, and the laws were repealed by the early 1930s. During this time period, community clinics that had been the go-to for individuals battling opioid or narcotic addiction were shut down. “Ambulatory” opioid addiction treatment, as well as the new specialty of addiction science, was all but wiped out for several years, and many suffering from addiction ended up in prison instead of getting the help they needed.[30]

Shift to Medical and Supportive Treatment

Between 1924 and 1935, those battling addiction to narcotic drugs may not have had many resources unless they belonged to the upper classes of society and could afford the new private hospitals’ detoxification services.[31] In 1929, in the face of extreme federal prison overcrowding and no real answers for addiction treatment, the Porter Act was passed that mandated the formation of two “narcotics farms” to be run by the U.S. Public Health Service. In 1935, one such prison/hospital providing addiction treatment for prisoners or those voluntarily seeking services opened in Lexington, Kentucky, while the second opened in Forth Worth, Texas, in 1938.[32] Up until the late 1950s, these two “farms” provided the majority of the addiction treatment services in the United States. They offered a three-pronged approach, including withdrawal, convalescence, and then rehab, all perpetuated by a medical and mental health team of experts.[33]Treatment for addiction moved out of the community-based and “goodwill” type facilities to a more clinical setting. As a result, addiction treatment services began to shift to a more medical approach.[34]

Between 1924 and 1935, those battling addiction to narcotic drugs may not have had many resources unless they belonged to the upper classes of society and could afford the new private hospitals’ detoxification services.[31] In 1929, in the face of extreme federal prison overcrowding and no real answers for addiction treatment, the Porter Act was passed that mandated the formation of two “narcotics farms” to be run by the U.S. Public Health Service. In 1935, one such prison/hospital providing addiction treatment for prisoners or those voluntarily seeking services opened in Lexington, Kentucky, while the second opened in Forth Worth, Texas, in 1938.[32] Up until the late 1950s, these two “farms” provided the majority of the addiction treatment services in the United States. They offered a three-pronged approach, including withdrawal, convalescence, and then rehab, all perpetuated by a medical and mental health team of experts.[33]Treatment for addiction moved out of the community-based and “goodwill” type facilities to a more clinical setting. As a result, addiction treatment services began to shift to a more medical approach.[34]

In 1935, the Oxford Group, a religious movement that believed in self-improvement methods enhanced by spirituality and shared within the community, was likely the beginnings of 12-Step support programs like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).[35] Narcotics Anonymous may have originated in one of the federal “narcotics farms” and may have started out as “Addicts Anonymous” that was slow to catch on but, over time gained popularity using AA models and methods of support.[36] By 1950, the Minnesota Model, which is a method of treating chemical dependency by both professional staff and supportive individuals in recovery themselves, had been introduced. The Minnesota Model was adopted by the not-for-profit Hazelden Foundation and employed an individual treatment plan that viewed addiction as a treatable disease through education, family involvement, a 28-day residential stay, and continuing support through AA participation.[37]

Consequences of Legislation and Laws on Drug Treatment

The possession and sale of narcotics were further criminalized in 1952 and 1956 with the passage of the Boggs Act and the Narcotic Control Act respectively, which came with high penalties for drug possession and the sale of narcotics.[38] Young people addicted to opioids, and particularly heroin, became increasingly more prevalent, especially in New York City, in the 1950s, and fueled the need for juvenile and adolescent drug treatment programs along with the concept that addiction was indeed a disease.[39] In 1952, New York City opened the Riverside Hospital specifically for adolescents addicted to drugs, although the programs proved largely ineffective, and the facility was not even open for 10 years.[40] Long-term residential options were considered, as relapse rates were so high, and therapeutic communities (TCs) were born – the first of which may have been the Synanon in California in 1958.[41]

TCs were, and still are today, residential communities where individuals struggling with drug addiction stayed for a long period of time with groups of people with like circumstances. They are self-supporting communities that maintain abstinence through self-help and supportive methods. When they first appeared, TCs did not allow for any type of mind-altering medications, much in the vein of AA methodology; however, today, TCs may allow for the use of maintenance medications when necessary.[42]

In the 1960s, methadone was introduced as an opioid addiction maintenance treatment, as it was a long-acting opioid that could be substituted for shorter-acting ones, such as heroin. A public health initiative sought a publicly funded opioid treatment system that heralded the use of methadone.[43] In 1964, the Narcotics Addiction Rehabilitation Act (NARA) of 1966 provided local and state governments with federal assistance for drug treatment programs intended for those addicted to narcotics. These programs were meant to provide inpatient services; however, due to overwhelming need, most patients were likely served with more cost-effective outpatient services that included weekly drug tests, counseling three times a week, dental restorative services, psych consults, vocational training, and methadone maintenance.[44]

While methadone was also deemed effective for opioid addiction treatment, it also carried a high rate of abuse and diversion. In the 1970s, further legislation controlled the dispensing of the opioid antagonist and brought it under federal control with the introduction of the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP) by President Nixon during his War on Drugs.[45] The Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act of 1970 set about to improve treatment for alcohol addiction via medical means by recognizing it as a possible disease instead of a moral failing of character, thereby opening up increased research into the subject.[46]

Coverage of Drug Addiction Treatment and Effects on Services

Between 1964 and 1975, insurance companies began to recognize addiction as a treatable disease and started providing coverage for treatment for those battling addiction. By the 1980s, drug addiction treatment and alcohol addiction treatment were finally seen as similar, and treatment efforts were merged.[47]

Between 1964 and 1975, insurance companies began to recognize addiction as a treatable disease and started providing coverage for treatment for those battling addiction. By the 1980s, drug addiction treatment and alcohol addiction treatment were finally seen as similar, and treatment efforts were merged.[47]

In 1985, specialized treatment options begin regularly appearing, catering to demographics such as the elderly, gay individuals, women, adolescents, and those suffering from co-occurring mental health disorders.[48]

In 1987, despite President Regan’s renewed War on Drugs campaign that sought to penalize drug abusers, the American Medical Association (AMA) declared drug dependence as a legitimate disease and demanded that it be treated no differently than other medical ailments.[49] Miami became home to the first “drug court” helping nonviolent offenders get into addiction treatment programs and avoid jail time.[50]

Hospital-based inpatient treatment centers were forced to close their doors between 1989 and 1994 after insurance ceased paying benefits. Addiction services were rolled into behavioral health services along with mental health and psychiatric conditions, opening the doors to a more outpatient or intensive outpatient approach as opposed to largely residential treatment.[51]

The emergence and resurgence of cocaine as a major drug of abuse with high rates of addiction may also have given rise to more intensive outpatient treatment options. By the mid-1990s, public funding and Medicaid recipients were provided with intensive outpatient services as the preferred method of treatment.[52]

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) of 2000 allows for the office-based treatment of opioid and narcotic addiction through medical maintenance drugs, and the prescription of controlled substances designed to help with detox and prevent relapse, such as buprenorphine opioid agonist products. It also allows for more leeway in treating addiction by an accredited facility.[53]

Perhaps the biggest piece of healthcare reform regarding mental health and addiction treatment came via the Affordable Care Act (ACA). As of 2014, the ACA includes substance abuse and dependence as one of the 10 essential health benefits to be treated as a medical condition and covered by insurance in the same manner as surgical or other medical procedures.[54]

Modern Drug Rehab

Scientific research has been ongoing for years into the causes, treatment, and optimal recovery efforts for drug abuse and addiction. The medical community today largely heralds the disease theory of addiction – that brain chemistry is altered through regular substance abuse, leading to behavioral changes and compulsory drug-abusing behaviors as well as the creation of a physical dependence that may be best treated by pharmacological and therapeutic methods.[55]

Most of the early forms of drug treatment have long been discarded, and even viewed as cruel and unusual punishments. The overriding theme today is that addiction can be treated through much more humane methods.

Many treatment models may have their roots in previous methods, however. Aversion therapy is still used today, although most often through medications like disulfiram that discourage individuals addicted to alcohol from drinking, and naloxone an opioid agonist that can precipitate opioid withdrawal if abused, therefore helping to prevent relapse.[56]

Detox is generally accomplished in either an outpatient or residential setting, depending on the severity of an individual’s dependence on drugs or alcohol. The more severe the dependency, the more intense withdrawal symptoms and drug cravings may be. More intense symptoms and cravings benefit from medical detox, with around-the-clock medical monitoring, care, and the inclusion of pharmaceuticals.

Other drug treatment programs beyond detox include:

- Prevention programs

- Outpatient programs

- Intensive outpatient programs

- Transitional programs

- Residential treatment programs

- Aftercare and recovery support programs

Prevention models are often seen in schools, community-based facilities, and organizations aimed at educating the public on the dangers of drug abuse and addiction. They aim to help individuals seek out treatment when necessary. Outpatient, intensive outpatient, transitional, and residential treatment programs may all include some of the same research-based methods in differing levels of structure and comprehensiveness. A residential program likely provides the highest level of care with 24-hour supervision and a high level of structure.

Behavioral therapy sessions are included in most drug treatment programs and usually include both group and individual sessions to introduce healthy coping mechanisms, and a better understanding of the interaction between thoughts and actions and how to modify them in positive ways. Families are often included in these sessions as well. Skills training sessions and educational opportunities may also be important components of modern drug treatment programs, as are counseling sessions. Programs like 12-Step groups pay a big role in recovery and aftercare, as they can help to build a supportive community around an individual battling addiction and help to prevent relapse.

Drug addiction treatment programs have come a long way over the years and continue to evolve as new research and scientific evidence come to light. Today, holistic and traditional methods are often blended to form a comprehensive treatment model that seeks to help individuals and families strike a balance between the mind, body, and soul while treating the whole person. Nutrition and physical wellbeing may be directly tied to emotional health. By addressing both physical and mental health, a strong recovery foundation can be formed.

Learn More About Addiction Treatment

- Medical Detox Centers

- Inpatient Rehab Facilities

- Outpatient Rehab Treatment

- Las Vegas Drug & Alcohol Rehab Centers

Citations

- (Sept. 2014). “Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Summary of National Findings.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Accessed November 7, 2015.

- (April 2011). “Definition of Addiction.” American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). Accessed November 7, 2015.

- (Dec. 2012). “Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide Third Edition.” National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Accessed November 7, 2015.

- Quinonies, MA. (1975). “Drug Abuse During the Civil War (1861-1865).” The International Journal of the Addictions. Accessed November 7, 2015.

- (2005). “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). Series, No. 43.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).Accessed November 7, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Brown, EM. (Jan. 1985). “‘What Shall We Do with the Inebriate?’ Asylum Treatment and the Disease Concept of Alcoholism in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. Accessed November 7, 2015.

- York, M. (April 2008). “Rescuing ‘the Castle’ from Some Dark Days, Architecturally and Medically.” The New York Times. Accessed November 7, 2015

- (1999-2001). “Before Prohibition: Images from the Preprohibition Era When Many Psychotropic Substances were Legally Available in America and Europe.” Addiction Research Unit. Department of Psychology University of Buffalo.Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (n.d.). “Fargo North Dakota: its History and Images.” North Dakota State University (NDSU) Libraries. Accessed November 8, 2015.

- (2003). “Quest for a Cure: Care and Treatment in Missouri’s First State Mental Hospital.” Office of the Secretary of State, Missouri. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Chiang, H. (April 2009). “An Early Hope of Psychopharmacology.” Princeton University. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Markel, H. M.D. (April 2010). “An Alcoholic’s Savior: Was it God, Belladonna, or Both?” The New York Times. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Acker, C. PhD., Kurtz, E. PhD., White, W. MA. (2001). “The Combined Addiction Disease Chronologies.” William White Papers. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- White, W. (1998). “Significant Events in the History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America.” Chestnut Health Systems. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Greenburg, D. (Sept. 2012). “10 Mind-Boggling Psychiatric Treatments.” Mental Floss Magazine. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- [18] White, W.L. (2002). “Trick or Treat? A Century of American Responses to Heroin Addiction.” Auburn House. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (2005). “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). Series, No. 43.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Lemere, F. MD. (1987). “Aversion Treatment of Alcoholism: Some Reminiscences.” British Journal of Addiction. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Schachter, M. MD. FACAM. (2014). “Causes of Adrenal Insufficiency.” Schachter Center for Complimentary Medicine. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Hamby, W.B. M.D., Mason, T.H. M.D. (April 1948). “Relief of Morphine Addiction by Prefrontal Lobotomy.” TheJournal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (2003). “Quest for a Cure: Care and Treatment in Missouri’s First State Mental Hospital.” Office of the Secretary of State, Missouri. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- White, W.L. (2002). “Trick or Treat? A Century of American Responses to Heroin Addiction.” Auburn House. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Kandall, S. MD. (1996). “Women and Addiction in the United States: 1850 to 1920.” National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Accessed November 8, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Brecher, E., editors of Consumer Reports Magazine. (1972). “Chapter 8. The Harrison Narcotic Act (1914).” Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Accessed November 8, 2015.

- Ibid.

- White, W.L. (2002). “Trick or Treat? A Century of American Responses to Heroin Addiction.” Auburn House. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Clark, J. (n.d.) “History of Rehab.” How Stuff Works. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (2015). “Over 80 Years of Growth.” Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Accessed November 9, 2015.

- White, W.L. (2002). “Trick or Treat? A Century of American Responses to Heroin Addiction.” Auburn House. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Anderson, DJ., DuPont, RL., McGovern, JP. (1999). “The Origins of the Minnesota Model of Addiction Treatment- a First-Person Account.” Journal of Addictive Diseases. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- White, W.L. (2002). “Trick or Treat? A Century of American Responses to Heroin Addiction.” Auburn House. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Winick, C. (Jan. 1962). “Maturing Out of Narcotic Addiction.” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (2005). “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). Series, No. 43.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (July 2015). “Therapeutic Communities.” National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Ibid.

- (2005). “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). Series, No. 43.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Rettig, RA., Yarmolinsky, A., editors. (1995). “Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment.” National Academies Press (US). Accessed November 8, 2015.

- Ibid.

- (n.d.) “History of NIAAA.” National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Accessed November 9, 2015.

- White, W. (1998). “Significant Events in the History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America.” Chestnut Health Systems. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- (2006). “Substance Abuse: Administrative Issues in Outpatient Treatment.” Centers for Substance Abuse Treatment. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (2005). “Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). Series, No. 43.” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (n.d.). “Substance Abuse and the Affordable Care Act.” Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP). Accessed November 9, 2015.

- (Spring 2007). “The Science of Addiction: Drugs, Brains, and Behavior.” National Institutes of Health. NIH Medline Plus. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- Williams, S. Ph.D. (Nov. 2005). “Medications for Treating Alcohol Dependence.” American Family Physician. Accessed November 9, 2015.

1800s: Addiction may have mostly been related to alcohol or opium; these substances may have been replaced with morphine, cocaine, or other supposed “medications” during addiction treatment.[10]

1800s: Addiction may have mostly been related to alcohol or opium; these substances may have been replaced with morphine, cocaine, or other supposed “medications” during addiction treatment.[10]