Who Are the Players in the Pharmaceutical Industry (Big Pharma)?

The term “Big Pharma” is used quite often to describe massive pharmaceutical companies that make literally billions of dollars every year to keep Americans regularly supplied with a medicine cabinet’s worth of pills. But when we say Big Pharma, who are the players in the pharmaceutical industry? Who is responsible for flooding neighborhoods and communities with addictive medication? Who are the agencies responsible for keeping them in check? How are other countries dealing with addiction treatment?

The Money of Medicine

There are two sides to the coin of this conversation: the pharmaceutical industry, which is responsible for the development, manufacturing, and marketing of drugs for use as medications; and Big Pharma, the colloquial (and often pejorative) term used to describe faceless corporations that push hugely overpriced drugs onto hapless and desperate consumers.

Some of the names of the biggest players in the industry may be familiar. Others may not ring as many bells, but with their market value, the relative anonymity works to their advantage. The Motley Fool provides a list of the companies doing the best business:

- Johnson & Johnson ($276 billion market value)

- Novartis ($273 billion)

- Pfizer ($212 billion)

- Merck ($164 billion)

- GlaxoSmithKline ($103 billion)

- Eli Lilly ($98 billion)

Those deep pockets allow pharmaceutical companies to spend astronomical amounts on advertising. In 2014, spending on advertising was worth $4.53 billion, representing an 18 percent year-by-year increase. Out of all the individual companies in the industry, Pfizer spent $1.4 billion on advertising. Eli Lilly, the company behind the erectile dysfunction medication Cialis, spent $272 promoting that drug alone.1

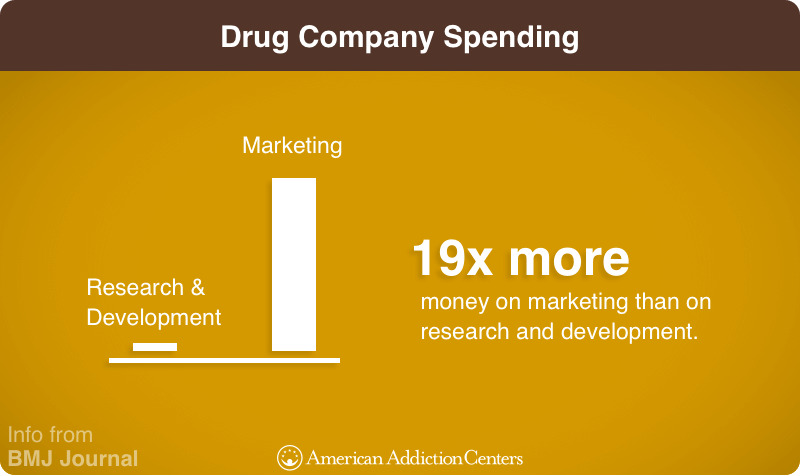

The highest amount paid in a single year on marketing pharmaceutical products was $5.4 billion in 2006. Ten years later, an ad aired during that year’s Super Bowl that was 60 seconds long and cost $10 million to produce but reached 111 million viewers.2 The BMJ Journal writes that drug companies spend 19 times more on marketing than they do on research and development.3

That’s a lot of money to spend on advertising, but io9 writes that every $1 spent on a commercial, billboard, radio, or print ad, brings over $4 in retail sales. For example, Boehringer Ingelheim spent $464 million in advertising for Pradaxa, its blood thinner, in 2011. In 2011, sales of Pradaxa passed $1 billion

Marketing Medicine

The investment is a sound one: Doctors prescribe new drugs that are featured in direct-to-consumer advertising nine times more than drugs that are not marketed publicly. This is because patients sometimes demand to be given the drugs they’ve seen in commercials (or heard about from their friends and family members), but also because some doctors receive handsome bonuses for promoting medications from certain manufacturers.4

The Wall Street Journal created an interactive graphic that showed how companies rewarded doctors – and by how much – in just the four months between August and December 2013:

- Promotional talks and honoraria: $228.1 million

- Travel, lodging, and entertainment: $95.9 million

- Food and drinks: $92.8 million5

One of the results of this spending avalanche is that pharmaceutical companies are seen and heard everywhere in the public sphere. “It’s true,” writes the Washington Post, “drug companies are bombarding your TV with more ads than ever.” Thanks to federal rules allowing drug companies to advertise directly to consumers, and an economic recovery after the Great Recession, pharmaceutical corporations have enjoyed their time in the sun. In 2014, television accounted for 61.6 percent of companies’ direct-to-consumer advertising revenue.6

The Wrong Side of the Law

The business of the pharmaceutical industry is not always a pleasant one. Given the fierce competition from rival corporations and the unfathomable amounts of money to be made, it is not surprising that some of the biggest federal fines ever levied have come against drug manufacturers.

In 2012, for example, GlaxoSmithKline pled guilty to criminal charges of willfully promoting its leading antidepressant drugs, like Paxil and Wellbutrin, to consumers under the age of 18. Neither drug had been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to be used by minors, for which reason the government slapped a $3 billion fine on the company. In 2012, Johnson & Johnson were hit with a $2.2 billion fine for promoting off-label use of its drugs (i.e., the company was found guilty of encouraging consumers to use the drugs for purposes not condoned by the FDA). Pfizer, in 2009, paid $2.3 billion for illegally marketing its Bextra drug. The New York Times noted that the fine – a “record sum” at the time – accounted for less than three weeks of Pfizer’s sales.7

With so much money at stake, it comes as no surprise that pharmaceutical companies are behind some of the biggest mergers and acquisitions in history. Pfizer purchased Warner-Lambert for $87.3 billion in 1993 (adjusting for inflation, about $125 billion in 2016). Pfizer’s goal was to have sole marketing leverage over the drug Lipitor, a medication to lower cholesterol. Crain’s New York Businesscalled Lipitor “the best-selling drug in the history of pharmaceuticals,” after the medication generated revenue of $1 billion in its first year and went on to produce $125 billion worth of sales in almost 15 years.8 The pharmaceutical industry has some very deep pockets; across the entire world, the medication market was worth $1 trillion in 2014, and a quarter of that revenue came from the United States alone, where five of the top 10 pharmaceutical manufacturing companies are located.

When the Pharmaceutical Industry Becomes Big Pharma

With those pockets comes a strong hand of political and legislative influence, to the tune of $2.9 billion between 1998 and 2014 on lobbying expenses, and $15 billion in campaign contributions between 2013 and 2014. For some people, this straddles the line between unethical and illegal. Even as the federal government issues massive fines to keep those companies in check, the industry itself is a significant contributor to the Food and Drug Administration’s budget, leading to concerns of conflicts of interest and outright bribery. This, say observers and watchdogs, is where “the pharmaceutical industry” becomes “Big Pharma.”

Science-Based Medicine wonders if Big Pharma’s influence reaches too far – not just to advertisers and lobbyists, but doctors willing to accept lucrative bonuses and scared patients demanding to be prescribed brand-name drugs for no other reason than seeing those names in the media. The very “psyche of the American people” is not immune to the weight of literally billions of dollars in spending money.9

The New American Mafia

It is for reasons like these that the Daily Beast referred to the pharmaceutical industry as “America’s new mafia,” leveraging enormous sums of money and brand-name recognition to put 70 percent of American consumers on medication.10, 11 Many of those people are members of vulnerable, at-risk demographics who either need medication to go about their daily lives or who do not have access to the information to determine whether or not expensive, potentially addictive medication will ultimately be good for them.

For Big Pharma, such people are ultimately consumers. Eleven companies in the pharmaceutical industry made $711 billion from price-gouging Medicare, the government program for seniors and disabled citizens, leading the Huffington Post to declare that Big Pharma is committing a robbery by overcharging taxpayers. Per capita drug spending in the United States is 40 percent more than it is in Canada, 75 percent more than it is in Japan, and nearly three times as much as it is in Denmark.12

In 2014, The New York Times quoted a professor of management practice at Harvard Business School, who asked whether the purpose of large pharmaceutical corporations was to research and develop drugs that can improve the quality of life for people, or – after Pfizer failed to buy AstraZeneca, a multinational pharmaceutical and biologics company for $119 billion – whether such entities existed “to make money for shareholders through financial engineering.”13, 14

Click Here to Learn More

Brand-Name vs. Generics

Another example comes from New Jersey, home to many giants of the pharmaceutical industry. One of them is Endo Pharmaceuticals, which was sued by the Federal Trade Commission in 2016 for illegally blocking the production of lower-costing generic versions of their drugs, Opana ER and Lidoderm.[17] In the Garden State, elderly and disabled residents are more likely to be prescribed brand-name drugs over basic generic drugs than in any other state in the country. The national average of brand-name prescriptions is 21.2, but that figure shoots up to 28 percent in New Jersey, a figure representative of what local doctors have called “wasteful overprescribing.”

Scientific American explains that the difference is not so much to do with the chemical composition or quality of the brand-name and generic drugs, but how they are regulated and priced. Brand-name drugs are obviously much more expensive than generics, even though generics can have acceptably similar effects on patients. The professor and head of the Department of Pharmacy Practice at the University of Connecticut, per The Huffington Post, “strongly recommends” that patients choose generic medications over brand-name products if possible, “since they almost always work as well and can save people a lot of money.”18

However, the companies that produce generic drugs often do not have the financial influence and spending power of the bigger pharmaceutical companies that produce the brand-name drugs.19 This, despite the FDA stating that nearly 80 percent of the prescriptions filled in the United States are for generic drugs, hinting at the unimaginable sway Big Pharma companies have over that market.20

With so much of the pharmaceutical industry housed in New Jersey, doctors there are exposed to a great deal more of the sway and leverage that Big Pharma can exert, leading to doctors eagerly writing prescriptions for brand-name drugs and receiving lavish bonuses for their efforts – sometimes in the form of free food and beverages, and other times in the form of private stadium suites at sporting events and dinner at five-star restaurants.21

Big Pharma’s Big Pockets

Patients can be complicit on their own, oftentimes overriding their doctors’ opinion about using a generic drug instead of an unnecessary brand-name counterpart. Consumer Reports quotes the Journal of the American Medical Association in noting that many doctors acquiesce to their patients’ demands.22 Researchers writing in the journal of Medical Care lament that patients who request a specific medication during their doctors’ appointments have the effect of “dramatically” increasing how often their physicians prescribe that particular medication.23

Speaking to NJ Spotlight, a doctor laments that Big Pharma corporations “have the government and the regulators in their pocket.”24

The Rise of the ‘Thought Leader’

The doctors who accept the overtures from pharmaceutical companies, and the companies who engage in the practice, see things a bit differently. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the trade group that represents the interests of the pharmaceutical industry in the US, is of the official position that the business between individual drug manufacturers and doctors, is to improve patient care through the advancement of shared interests in pharmaceutical care.

One way this is done is by the work of doctors speaking to other doctors, either in one-on-one settings or at symposiums and seminars. A doctor in this role is known as a “thought leader,” someone who is paid by a pharmaceutical company to talk to other doctors about a drug, or drugs, manufactured by that company.25

In “How to Win Doctors and Influence Prescriptions,” NPR writes that the term thought leader is widely understood to be a euphemism. Even as Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America looked to scale back on some of the more excessive methods used to court doctors, the trade group still left the door open for a more subtle way to spread their message.

The Psychology of Making Leaders out of Doctors

Instead of suite seats at sports stadium, pharmaceutical companies turned to doctors themselves, asking physicians to become speakers at upscale restaurants and hotel conference rooms. The doctor’s role is to educate their colleagues on the advantages and disadvantages of a particular drug, for which a handsome fee is paid out. The nature of the role is explicitly laid out by the company paying the doctor for the work: The doctors are trained to present the drugs in a very specific way, using psychologically precise language that will appeal to the communal sense that the gathered doctors all share. NPR notes that all the pharmaceutical representatives they interviewed for their story “used the exact same phrase” when talking about how doctors were prepared for their roles as thought leaders.

One doctor tells NPR that his role is to increase education and awareness of new drugs hitting the market. The money is nice, he says, but the satisfaction comes from teaching other doctors how they can help their patients.

This ego boost provides a veneer of insulation against the work that pharmaceutical reps used to do: go to hospitals and clinics and try to woo harried and busy doctors with free samples and glowing statistics, typically greeted with “disdain and abuse.”26 Some doctors would even ban reps from their professional premises.

When a thought leader does it, however, usually in a setting that is much nicer than a doctor’s office or a hospital, there is a sense of advancing a cause larger than themselves; they do it in the name of academics and in the name of medicine. That feeling of inspiration suggests a new direction that the pharmaceutical industry is adopting, but one former representative speaking to NPR admits that not much has changed. The definition of a thought leader is “a physician with a large patient population who can write a lot of pharmaceutical drugs.”27

Pleading Guilty and Paying Fines

Driven by literally billions of dollars’ worth of research and advertising, the modern healthcare system seems stuck between those who want to legitimately advance medicine and those who want a piece of the very rich pie. Writing about the $1.4 billion settlement that Eli Lilly reached with the federal government, ProPublica notes that sales representatives acting on behalf of the company encouraged physicians to promote “off-label” uses of the Zyprexa drug. Since such uses are not approved by regulating like the Food and Drug Administration, the sales reps and the doctors who did what they were told were in violation of federal law.28

Lawsuits from whistleblowers – usually disgruntled former sales representatives, fed up with the cutthroat business practices – have highlighted other dishonest practices from companies in the pharmaceutical industry. For example, Allergan, the manufacturers of Botox, hosted over 200 doctors at an oceanfront resort in California who were paid $1,500 to do nothing but listen to presentations. Allergan agreed to a government settlement for $600 million and offered a misdemeanor guilty plea for misbranding Botox.29

Elsewhere, sales representatives of Forest Laboratories leaned on doctors to prescribe Celexa and Lexapro under the guise of participating in a program where they would merely “observe” the doctors – who, in turn, were paid up to $1,000 each for their participation. A subsidiary of Forest Laboratories pleaded guilty to felony and misdemeanor charges, and the company itself paid $313 million in combined criminal and civil penalties.

Illegal Promotions and Public Disclosures

Similarly, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals – owned by Pfizer – was accused of hiring speakers on the basis of how often they prescribed one of the company’s drugs. Two former sales reps went on record as saying that the corporation’s management not only “exclude[d] speakers who did not promote [the drug]” but also rewarded those who did so with multiple speaking engagements and payments.

Wyeth Pharmaceutical’s method of dealing with dissenting doctors – those who had unfavorable or enthusiastic opinions about the drug – was to have sales representatives “counsel” the doctors on how they could treat the medication with greater favor.

Some pharmaceutical companies don’t even bother with the counseling. A complaint in 2008 against Cephalon accused the company of

rewarding poor speakers, as long as they “heavily prescribed” the drugs produced by the company. Some doctors were paid to attend public speaking training sessions even though there was no plan to make the doctors actually

speak at seminars or gatherings. Other doctors were paid when there were no audience members in attendance. Even good public speakers were dropped by Cephalon if it was found that they did not write “substantial off-label prescriptions.” Cephalon pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of selling misbranded drugs and paid $425 million in fines. The terms of the settlement included Cephalon having to publicly disclose the nature and amount of payments it made to doctors.30

Purdue Pharma and the American Opiate Epidemic

Big Pharma has raised a lot of eyebrows for the money it can throw at doctors and legislators, but perhaps the most serious effect it has had on American healthcare is the epidemic of the overprescription of powerfully addictive drugs. A 2011 survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed that Americans aged 19-64 were prescribed an average of 11.9 prescriptions, and Americans 65 and up received an average of 28 prescriptions. The United States makes up only 5 percent of the world’s population but consumes 80 percent of the painkillers in the world.

A staggering number of those painkillers bear the watermark of one pharmaceutical company. That same company started what The Week calls “the American opiate epidemic,” thanks to a relentless marketing strategy that downplayed the true nature of the drug being produced.31 In 1995, the Food and Drug Administration gave the nod to Purdue Pharma, a private, family-owned company in Stamford, CT, to produce OxyContin, the brand name of the generic form of oxycodone, a semisynthetic opioid. It took one year for OxyContin to generate $45 million in sales. By the beginning of the following decade, sales passed $1 billion; by the end of that decade, sales passed $3 billion. In 2010, Purdue Pharma owned one-third of the painkiller market in the United States, all thanks to OxyContin.32

To get to that point, Purdue Pharma had a lot of help. The company went from employing 318 sales representatives in 1996 to 671 in 2000. To better push OxyContin to doctors and “thought leaders,” those sales reps received yearly bonuses to the tune of $70,000; some saw their bonuses pass $250,000. In 2001, after OxyContin logged sales of $1 billion, Purdue Pharma’s expenses on promoting the drug to doctors passed $200 million. The company even created a list of doctors who, based on precedent, were likely to prescribe pain medication to their patients and actively pursued those doctors.33

Fishing Hats, Stuffed Toys, and Coupons for Free Prescriptions

Between 1995 and 2000, Purdue Pharma hosted 40 “pain conferences” in resorts that catered to primary care physicians and doctors who specialized in cancer treatment. The company arranged for more than 2,500 physicians to deliver (paid) speeches and presentations at the conferences. In a single year (2001), Purdue put down $4.6 million to advertise OxyContin in medical journals.

A Government Accountability Office report published in 2003 revealed that Purdue Pharma “distributed several types of branded promotional items” to doctors and physicians, including:

- OxyContin fishing hats

- Stuffed toys

- Luggage tags

- Music CDs

- Coffee mugs with heat activated messages

The company even created a program whereby doctors could distribute coupons to their patients for free, single-use OxyContin prescriptions.34

The unbelievable sums of money paid off. OxyContin prescriptions in 2002 were ten times higher than those in 1997. To keep up with the ravenous demand, the FDA approved Purdue Pharma increasing the dosage per pill, doubling the 80 mg original to 160 mg.

The Truth behind OxyContin

All this masked an ugly reality: The effects of the OxyContin wore off much sooner than the magical 12-hour duration, a fact that Purdue Pharma knew very well. According to an in-depth report from the Los Angeles Times, Purdue Pharma knew about it when the drug was going through clinical trials in the mid-90s. When doctors started to prescribe shorter doses to ensure that their patients didn’t start to withdraw from their drug therapy, sales representatives – acting on orders from Purdue’s executives – instead encouraged (and incentivized) doctors to prescribe stronger doses. The Times explains that the key reason OxyContin enjoyed such market dominance in the crowded painkiller market was because of its promise of 12-hour relief. Take that away, and not much separates OxyContin from less expensive painkillers.35

A deception on that scale couldn’t be covered up for very long, especially as more and more Americans started abusing OxyContin, stealing pills, and forging prescriptions, and unscrupulous doctors were more than happy to oblige. When the OxyContin became too much to afford, and the need to take more drugs became too much to resist, people turned to deadlier alternatives.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that in 2001, around 2,000 people overdosed on heroin across the United States. By 2013, heroin claimed about 8,000 lives.36 As the trade and death count of heroin increased, so too did the number of deaths related to overdosing on prescription opioids, like Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin. There were 6,000 such fatalities in 2001; by 2013, there were 15,000.37 The National Survey on Drug Use and Health discovered that 80 percent of heroin users started out on opioids, dramatically changing the demographics of drug use across the country.38

The trail of death and misery led back to OxyContin, which led back to Purdue Pharma. In 2007, the Department of Justice initiated proceedings against Purdue in federal court, on charges of misleading doctors and patients by claiming that OxyContin was less likely to be abused than other forms of narcotics. Purdue admitted that they misbranded OxyContin as “abuse resistant” and paid $600 million in fines – an amount that Pacific Standard magazine says “would have little effect on the company’s revenue.”39, 40 Even after three company executives paid $35.4 million in individual fines, OxyContin still makes $3 billion every year for the company. The Sackler family, which privately owns Purdue Pharma, is worth $14 billion, amounting to the 16th-largest fortune in the United States.41

Is Big Pharma Going to Get Bigger?

In 2014, ProPublica wrote that the total amount that pharmaceutical companies have agreed to pay the Department of Justice in fines and penalties for fraudulent market practices, such as promoting medications for uses that violate the approval standards of the Food and Drug Administration, exceeded $13 billion.42

The colossal figure not only speaks to the severity and scope of the worst of Big Pharma, but also to the dizzying heights of the financial influence that the companies in the pharmaceutical industry wield. These companies can be individually docked in the hundreds of millions of dollars to even a few billion dollars, but still recoup those losses in a matter of weeks. Even as the corporations admit culpability and promise to do better next time, their products flood hospitals and pharmacies, medicine cabinets, and gym bags. Marketing blitzes and millions of dollars thrown at primetime commercial spots ensure that, for all the lawsuits and negative press, Big Pharma is not going to get smaller.